“I should emphasize that we do not measure the progress of our investments by what their market prices do during any given year. Rather, we evaluate their performance by the two methods we apply to the businesses we own. The first test is improvement in earnings, with our making due allowance for industry conditions. The second test, more subjective, is whether their “moats” – a metaphor for the superiorities they possess that make life difficult for their competitors – have widened during the year.”

~ Warren Buffett

Will you indulge me for a corny nautical metaphor? Let’s give it a try…

Imagine you’re crossing the ocean by boat. You spend the first 20 minutes of the journey staring out at the sea, marveling at its beauty. Then you get bored, start to feel nauseous, and spend the rest of the trip in your cabin concentrating on every wave as it sways you back and forth, up and down.

The waves, of course, have almost no impact on the ship’s destination. That will depend on its heading, its speed, the trip length, and the underlying current. It will also depend on the skill of the captain and the quality of the ship. But it’s easy to forget about all that while you’re retching in a bucket.

This seems to be how many investors approach the stock market. They are very focused on the daily ups and downs of stock prices. They don’t pay nearly enough attention to the fundamental drivers of long-term returns.

Total Return = Earnings Per Share Growth + Price/Earnings Change + Dividend Yield (+ Interaction Terms)

The formula above provides a simple breakdown of the drivers of total return for a stock (or a portfolio of stocks). It will work just as well if you replace “earnings” with free cash flow, dividends, revenue, or book value.

To outperform a broad-market benchmark like the S&P 500, a portfolio needs to be better than the benchmark along at least one of these dimensions: faster earnings growth, greater expansion (or less contraction) in the price/earnings multiple, and/or a higher dividend yield. When these factors are moving in the same direction, the compounding effects can be powerful.

I’ve found that changes to the P/E ratio have an outsized impact on short-term returns, but their effect diminishes over time. The opposite is true for earnings growth: It’s relatively less important in the short run, but starts to dominate the total return equation over longer holding periods.

Say a company grows earnings per share 12% annually, but its price/earnings ratio contracts from 20 to 15. If that happens in one year, the stock will be down 16% (=12% earnings growth, minus 25% from P/E contraction, minus 3% from the interaction between the two). However, if the same thing happens over 10 years instead, the total return will be positive 8.8% per year. The P/E contraction goes from a sudden shock to a mild 3.2 percentage point annual headwind.

This is one of the reasons it’s so important to have a long-term investment horizon. Short-term movements in the price/earnings ratio are unpredictable because they depend on investor sentiment. Forecasting long-term earnings growth isn’t easy, but with diligent research and thoughtful analysis we can hopefully get in the ballpark.

If I had to summarize our strategy for Trajan’s Expanding Moat and Defensive Moat strategies in one sentence, this would be it: We try to grow our portfolios’ aggregate earnings significantly faster than the S&P 500, without giving too much back from price/earnings multiple compression. That’s easy to say but hard to execute. It requires identifying companies with durable competitive advantages, a long growth runway, trustworthy management, sound balance sheets, and reasonable valuations.

Google: One of the All-Time Greats

Alphabet GOOG/GOOGL, the parent company of Google, is a classic example of what we’re looking for. It is one of the largest positions in both Expanding Moat and Defensive Moat, and I think the stock offers a favorable risk/reward tradeoff.

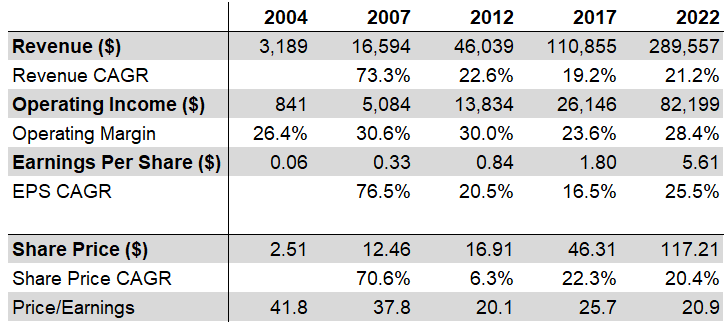

Let’s start with where Alphabet has been. The company was founded in 1998 and had its initial public offering on Aug. 19, 2004. Adjusting for stock splits, it closed its first day of trading at $2.51 per share. As of Aug. 19, 2022—18 years after the IPO—the Class A shares (ticker GOOGL) were trading for $117.21. That’s a 47-fold return, or about 24% per year.

Below is a table of key financial data for Alphabet presented in five-year increments, plus the year of the IPO. The 2022 figures reflect consensus estimates according to Bloomberg. Since 2004, Alphabet’s earnings per share compounded at almost 29% per year. That was faster than the stock’s 24% annual return because of price/earnings multiple compression. The P/E fell by half over these 18 years, which created a roughly five percentage point annual headwind to returns. This is typical with growth stocks: We’re usually betting that earnings growth will more than offset a decline in the P/E.

Exhibit 1: Earnings Growth Drives Total Returns at Alphabet

CAGR refers to compound annual growth rates in revenue, earnings per share, and the share price between the years listed. Numbers may be adjusted for divestitures, extraordinary legal charges, nonrecurring tax provisions, and similar items. Per-share amounts have been adjusted for stock splits. The share price is for the Class A shares as of the close on Aug. 19 of each year or the closest trading day. Price/earnings ratio divides the share price shown by the full-year earnings per share. Figures for 2022 reflect consensus estimates, according to Bloomberg, as of 8/22/22. Source: Bloomberg, Trajan estimates.

Taking a longer-term perspective helps us focus on the underlying drivers of returns—the ship’s heading and speed instead of the waves. The table above makes it look like Alphabet has enjoyed smooth sailing over the last 18 years. When you zoom out, it’s easy to forget about the many storms along the way: The financial crisis, the housing crash, the coronavirus pandemic; ups and downs in GDP growth, interest rates, foreign exchanges rates, consumer sentiment; and fears that Google would be disrupted by smartphones, vertical search services, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, or TikTok.

A Widening Moat

Much of Google’s historical growth was the result of being in the right place at the right time. The Internet became the world’s primary source of information, and Google had the most efficient way to organize and present that information. Advertisers who wanted to reach all those new Internet users found Google was the best place to do it.

The company’s core search advertising business is a masterpiece. Users tell Google exactly what they’re looking for. The incremental cost to provide an answer—originally a series of links but increasingly a customized response, depending on the query—is approximately zero. Google had to spend billions of dollars on servers, network capacity, and research & development to improve its algorithms and machine learning technology, but once all of that is in place, responding to one more query is basically free (aside from revenue sharing with partners).

For requests with commercial intent—like “hotel in Phoenix” or “cheap car insurance”—advertisers bid in an auction for the top few search results. From the advertisers’ perspective, they are getting access to a highly engaged, targeted audience at the exact moment when consumers are looking to buy something. From the users’ perspective, they’re getting helpful information in response to their query, which is much less intrusive than other forms of advertising.

Google’s competitive advantage starts with its brand and consumer habits. People started searching on Google because it was faster and had better-quality information than competitors, but now they mostly do it out of habit. There are no switching costs on the Internet; Google management famously said that “competition is only one click away.” But established routines can be just as hard to compete against, especially when there’s no financial incentive to try something new.

Alphabet has reinforced its moat by continually improving search results. It deepened its customer relationships with products like Chrome, Maps, Gmail, and Google Photos. The blockbuster acquisitions of YouTube and DoubleClick laid the foundation for a push into video advertising and serving ads to third-party websites. The company’s investment in Android proved especially foresighted, giving it priority access to the majority of global smartphone users.

Lastly, the competitive advantage that would be hardest to replicate is Google’s data. It’s been interesting to watch Facebook attract so much negative media and regulatory attention for allegedly violating consumer privacy, while Google often seems to get a free pass. Google knows far more about its average user than Facebook does, including your search history, your location history, the content of your emails, and more. The company can use this information to make its products more relevant and efficient every day. Since data is the critical input to developing artificial intelligence, Alphabet also has a big head start in that field.

Recent privacy changes may enhance Google’s competitive position. Apple has made it much harder to share data with third parties on iOS, and global regulation seems to be moving in a similar direction. But Google has a direct relationship with its users and more than enough first-party data, which should extend its lead over peers.

Unpulled Levers Create Future Opportunity

What makes me most enthusiastic about Alphabet—and the reason it’s a large position in the portfolios I manage (including my personal portfolio)—is that all the positive attributes described above don’t seem to be reflected in the stock’s valuation. As of the close on Sept. 2, with the Class A shares trading for $108, Alphabet is valued at 16.6 times consensus earnings estimates for next year—about in line with the S&P 500.

I think it’s likely that Alphabet can grow revenue faster than global GDP for the foreseeable future. Advertising spending has historically grown about in line with the broader economy, but digital advertising is displacing legacy media, and Google’s share of digital ads should be stable or improving. There’s a case to be made that advertising will become more important to the economy over time as digital ads replace other ways of attracting customers, such as operating retail stores or hiring salespeople. The improved targeting and measurement made possible by digital ads have also expanded the customer base to include smaller businesses that may have found TV or radio ads too expensive and ineffective.

Alphabet can further accelerate growth with non-advertising revenue sources such as Google Cloud, YouTube subscriptions, and the Google Play app store. If some of its “other bets” pay off—including Waymo self-driving cars, Wing delivery drones, or its healthcare ventures—that would be an added bonus. Over the longer run, I’m most intrigued by artificial intelligence, which has the potential to be the most transformative technology of our time. Alphabet is a clear leader in AI research—for example, its AlphaFold project recently announced that it had predicted the 3D structure of nearly all known proteins based on their amino acid sequence.

That said, we don’t need any of Alphabet’s more esoteric bets to work out for the stock to be a good investment. Google’s core business is so attractive that I don’t think management has ever made a serious effort at controlling costs or optimizing the capital structure. A Wall Street Journal analysis found that Google had the highest-paid employees among the companies surveyed, with a median salary of nearly $300,000 per year. Although the company hires many of the smartest people in the world, there are also plenty of anecdotal reports of unproductive workers and wasteful spending. Alphabet has shown no discernable operating leverage over the last 18 years, but if management made it a priority, I suspect they could materially increase margins in the core business. Elsewhere, Google Cloud remains unprofitable as the company focuses on locking in new customer relationships and gaining scale, while the “other bets” segment is losing well over $1 billion per quarter. Just eliminating those two drains on the income statement would boost earnings by more than 10%.

The capital structure is a similar story. Alphabet historically allowed its abundant free cash flow to pile up on the balance sheet. The company has never paid a dividend, and only recently has management started to get serious about share repurchases. As of June 30, Alphabet had about $110 billion of cash and equivalents, net of debt. If management were so inclined, they could use, say, 90% of the net cash to repurchase shares, boosting EPS by another 5% or more. If they were willing to shift to a net debt position—which the company could easily afford—the EPS benefit would be greater.

To be clear, I don’t expect management to take my suggestions, and they might not even be in the company’s long-term best interest. However, it’s important to keep these factors in mind when comparing Alphabet’s price/earnings ratio to alternatives like the S&P 500. Management teams have a variety of levers they can pull to create shareholder value: Selling or shutting down unprofitable divisions, letting go of unproductive employees, returning excess cash to shareholders, and so on. At Alphabet, most of these levers haven’t been pulled yet.

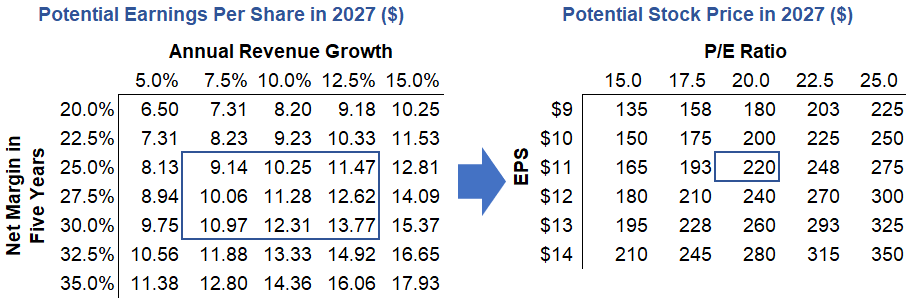

In the tables below, I attempted to come up with some reasonable scenarios for Alphabet’s earnings per share and stock price five years from now. As a starting point, I took the 2022 consensus revenue estimate of $289.6 billion and the adjusted net margin of 25.6% (adjusted net income divided by revenue). I figure that revenue will likely grow between 5%-15% per year, and that 20%-35% is a reasonable range for the net margin. I assumed the share count will decline about 3% per year. Lastly, I took the middle of the EPS range and assumed a terminal P/E ratio between 15 and 25 (I’ll share more thoughts on how to interpret P/E in a future post).

Exhibit 2: Possible Scenarios for Alphabet’s EPS and Stock Price in Five Years

Source: Trajan estimates.

Starting from a stock price of $108, I don’t think we need heroic assumptions for Alphabet to double over the next five years. For example, that could happen if the company grows revenue 10% per year (well below historical norms), achieves slight net margin expansion to 27.5% (minor efficiency improvements), and maintains its current-year price/earnings ratio around 20x. This scenario is highlighted by the blue boxes in Exhibit 2. More conservative assumptions could still be consistent with a double-digit annual total return. If management really started pulling all those levers, a 20%-plus annual return might be possible.

Risks

Every investing decision requires weighing the risks against the potential rewards. In Alphabet’s case, I believe the biggest risk is regulation. The company has been fined billions of dollars for alleged antitrust violations in Europe, and there are growing calls for similar actions in the U.S. Regulation could also address Alphabet’s use of personal data and accusations of bias in the way it moderates content. There have even been proposals to break up the company, which could make it harder to share data across product segments and increase costs for things like network capacity.

I have mixed feelings about the regulatory scrutiny of Alphabet. On the one hand, the company is immensely powerful, so regulation is a necessary counterbalance. We wouldn’t want Google preventing innovative new apps from accessing Android phones, interfering with elections by biasing search results, or failing to secure our personal data.

On the other hand, it would be easy for regulators to overreach in a way that makes Google’s services less useful to everyone. For example, I love Google Shopping’s carousel of image ads. Search for “lamp,” and you’ll be greeted by a scrolling row of lamp pictures along with prices, star ratings, shipping information, and links to purchase on third-party websites. Google Shopping has gotten a lot more useful lately as the company has allowed unpaid listings in addition to ads, broadening the selection. One of the antitrust actions in Europe alleged that Google Shopping represented unfair competition to other “comparison shopping” websites; sometimes, it seems like European regulators would prefer the company stick to blue hyperlinks forever. Google has generally been able to work around such regulations—in this case, they enabled comparison shopping sites to bid for image ads alongside Google Shopping—but if regulators push too far, it could harm both the company and consumers.

I think competition generally does a better job than regulation at keeping Alphabet in check. Management was right about competition only being one click away. That could mean other search engines like Microsoft’s Bing or privacy-focused DuckDuckGo, but the more interesting competitive attack comes from companies taking an entirely different approach to surfacing information. For example, there have been reports of young people turning to TikTok and Instagram for restaurant recommendations or vacation ideas, instead of searching on Google.

Competition fears seem to resurface every few years as new technologies are introduced. For a while, it was voice assistants like Amazon’s Alexa and Apple’s Siri. Before that, it was vertical search services on mobile—for example, many consumers now go directly to Amazon’s app when shopping or Booking’s app when researching hotels. The business of serving ads to third-party websites is intensely competitive, and this is one area where Alphabet may be inhibited by privacy rules that make it harder to share data across services. YouTube faces growing competition from all sorts of entertainment alternatives, from social media and streaming video, to video games and spending time with friends. I believe the reason competition hasn’t noticeably harmed Alphabet’s historical financial results is that “finding information” is an enormous use case, with room for many successful companies.

Another potential risk is a change to Google’s relationship with Apple. The company is rumored to pay Apple as much as $15 billion a year to be the default search engine on iOS. Apple could switch to a competitor or bring search in-house, either for its own business reasons or because it’s forced to by regulators. The impact on Alphabet would depend on how many users chose to manually switch their search engine back to Google instead of the default, and whether lost revenue exceeded the savings from not having to pay Apple anymore.

Lastly, the biggest factor weighing on Alphabet’s stock over the past few months seems to be investor concern about the cyclical nature of advertising. There will be less demand for advertising in a weaker economy, but this is a short-term worry that shouldn’t really matter over a five- or 10-year investment horizon, in my view.

If you’re interested in learning more about how Trajan Wealth can help you meet your financial goals, please click here or call 1 (800) 838-3079.