Some technologies profoundly change human civilization. The printing press. Electric lightbulbs. Radio and television. The Internet. Artificial intelligence feels like the next great innovation of that magnitude, and 2022 may be remembered as the year ordinary people started waking up to the possibilities.

AI has been used behind the scenes for years: It helps Google return relevant search results, Facebook decide what to show in your feed, and Uber to plan optimal routes. But 2022 brought a new wave of applications where consumers could interact with artificial intelligence more directly. OpenAI has been a leader in this field, with its ChatGPT application for generating text and Dall-E 2 for generating images. Click the links to give them a try, they’re free to use (for now).

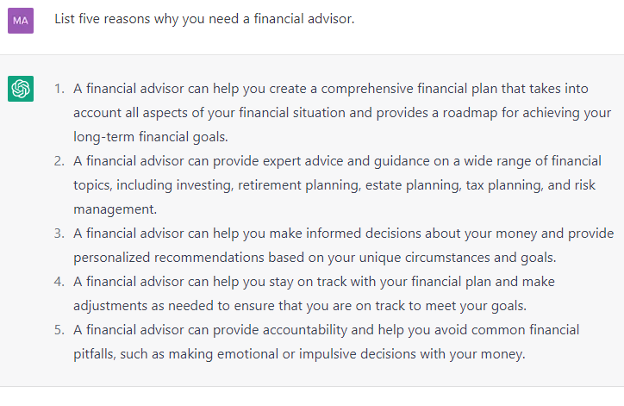

As an example, I asked ChatGPT to list five reasons why you need a financial advisor. Here’s what it came up with:

Chat GPT example

Not bad! ChatGPT sounds well-spoken, and it provided a concise and sensible list in response to my prompt. It took about 45 seconds to come up with this result. To be clear, it’s not copying the content from anywhere in particular—it’s using its knowledge base (mostly from the Internet) to craft an original answer in its own words.

Image generation works similarly. I asked DALL-E 2 for a picture of a financial advisor meeting with a client:

How Dall-E 2 imagines a financial advisor

This isn’t a real person, even if he does look like a few advisors I know. The hands are a giveaway—I think I count six fingers on his right hand, possibly seven? The chair is also missing an arm that would probably get in the way of where he’s sitting. But it’s still impressive that an AI algorithm could render this image from a one-sentence prompt in under a minute. You can also get more creative: How about a financial advisor meeting with a client in the style of a Van Gogh painting?

Advisor meeting in the style of Van Gogh

Keep in mind that this technology is still in its infancy. I expect exponential improvements in the coming years.

ChatGPT And Google

It doesn’t take much imagination to see how disruptive artificial intelligence could be, and also the scale of the opportunities it may create. From an investment perspective, those two things go hand in hand: Companies most at risk of disruption from AI could also be among its biggest beneficiaries, if they execute well.

Consider Alphabet’s GOOGL Google Search. One of the first reactions many people had to ChatGPT is that it could make Google irrelevant. Why should I stumble through dozens of links when I could just ask ChatGPT and get the answer to my question immediately?

That’s a risk, but I think the question reflects a misunderstanding of the nature of Google Search. Only a small fraction of queries are for factual information with a single correct answer. Most of the time, Google can already answer these queries directly. Type “How high is Machu Picchu?” into Google Search and you’ll get the answer right at the top of the results—7,972 feet. But the Google results include so much more: Maps and directions, pictures and videos, reviews from travelers, ads for tour companies, other questions you might find relevant, and links to more than 30 million external websites for additional reading. These are all identifiable sources, where users can make an independent judgment about the quality of the information. Better yet, Google returned all of this in less than a second, for free.

I don’t doubt that there will be some queries where a ChatGPT-like experience might be better. But what’s to stop Google from incorporating an AI chatbot in its own results, as needed? I strongly suspect that Google already has this capability. The company was responsible for much of the foundational research that made ChatGPT possible, and Google has demonstrated its leadership in artificial intelligence across several other disciplines. It uses similar text-generation technology with, for example, Google Translate or the “autocomplete” feature in Search and Gmail.

I can think of at least four reasons this hasn’t happened already: cost, latency, timeliness, and accuracy. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman has said that the cost of each ChatGPT conversation is “probably single-digits cents” because of all the computing power it requires. While that might not sound like a lot, it would be prohibitively expensive for a company like Google that responds to billions of searches every day. It’s only a matter of time before OpenAI has to start charging for its tools to offset these costs.

Latency refers to the time it takes to get results to a query. ChatGPT and Dall-E 2 both took around 30-60 seconds to respond to my test prompts. That’s intolerably slow for Google, which is accustomed to providing results in less than a second. ChatGPT also only has access to the year-old data it was trained on. Incorporating real-time data, as would be necessary for Google, would likely slow it down significantly while also increasing costs.

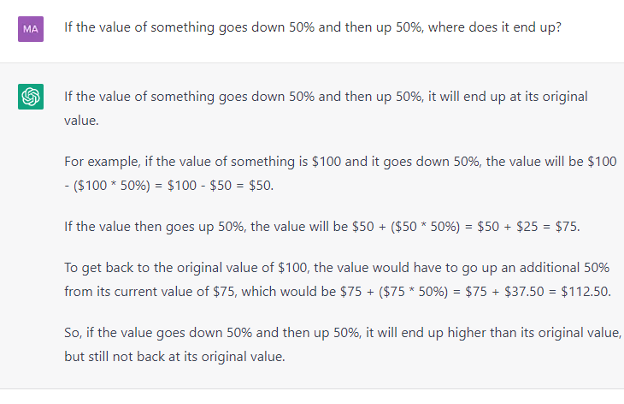

Finally, the biggest hurdle is that ChatGPT regularly returns confident-sounding answers that are completely wrong. That’s because it doesn’t really understand what it’s saying—it’s just putting words together in a way that seems to make sense in other contexts. As Mark Twain famously said, “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.” Check out this totally incoherent response to a simple math question:

ChatGPT is bad at math

I don’t think Google has much to worry about in the near term, but it may be a different story as these tools rapidly improve. Cost and latency are likely to fall with optimizations to semiconductor designs and model efficiencies. That should also improve timeliness and accuracy. When the technology is good enough, I’d expect Google to selectively start incorporating a chatbot in Search—not in response to every query, but when it thinks the chatbot will provide the best answer. Since consumers will continue to use Google for other kinds of searches, using the Google chatbot will be the path of least resistance. Of course, that all depends on Google’s management executing well, but when can you ever rest on your laurels in the technology sector?

Opportunities And Disruption

Almost every industry will be affected by artificial intelligence to at least some extent. Here are a few other areas where I see both opportunities and risks…

Semiconductors And Cloud Computing

AI requires a tremendous amount of computing power, and the demands are growing exponentially with each new model generation. We own Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing TSM in both our Expanding Moat and Defensive Moat portfolios. The company is (by far) the most important manufacturer of leading-edge integrated circuits, and it stands to benefit from increased demand for high-performance computer chips. As TSMC tests the limits of physics, competitors are struggling to keep up, though the potential for a Chinese invasion of Taiwan is a key geopolitical risk.

Another way to gain exposure to the semiconductor industry is through chip designers. The leader in AI computing has been NVIDIA NVDA, with its best-in-class graphics processing units (GPUs). Advanced Micro Devices AMD and Intel INTC are also hoping to participate in this market, along with any number of startups. NVIDIA has major advantages from its CUDA software ecosystem and accumulated know-how. There are also economies of scale in semiconductor design, since you can design a chip once and then produce many copies. On the other hand, it’s possible that artificial intelligence may disrupt these advantages—chips are getting so complicated that the computers increasingly need to design themselves.

The other way that Trajan’s Moat portfolios participate in the hardware side of AI is by investing in the leading cloud-computing platforms: Amazon’s AMZN AWS, Microsoft’s MSFT Azure, and Alphabet’s Google Cloud. Few users of AI will want to spend billions of dollars on proprietary supercomputers. Instead, most will rent access to the needed computing power from the big cloud vendors, who can share the hardware across many customers. Microsoft made a smart early investment in OpenAI, which enabled Azure to become OpenAI’s preferred cloud partner. It seems likely that Alphabet will also expose more of its AI tools to third-party developers through Google Cloud.

The leading cloud computing platforms have enough scale that it could make sense for them to design their own semiconductors, too. AWS is doing this with its Graviton, Trainium, and Inferentia chips, and Google has its Tensor Processing Units. By optimizing the chips for specific use cases and cutting out NVIDIA’s healthy gross margin, proprietary chips have the potential to be both faster and cheaper. The tradeoff is that it can require users of the chips to re-write large portions of their software. Whether NVIDIA is able to stay on top in this field will be one of the more interesting dynamics to watch in the coming years.

Programming And Design

GitHub Copilot, developed by Microsoft in partnership with OpenAI, may be the most successful commercial product to emerge from the latest wave of AI innovation. Copilot offers “autocomplete” suggestions as programmers write code. GitHub CEO Thomas Dohmke has claimed that Copilot is already writing 40 of every 100 lines of code for its users, and that it can cut project times by more than half. As with ChatGPT, Copilot is not a perfect tool—it requires human supervision to avoid introducing mistakes into the code—but the productivity benefits are enormous. As a Microsoft shareholder, I’m glad to see the company being so proactive about using the latest technology to improve its software. Copilot’s rapid adoption also shows the value of incorporating AI in existing workflows, instead of convincing customers to try an entirely new product.

Design software may be next. Rather than having a professional designer spend hours in Adobe’s ADBE Creative Cloud perfecting an image, what if you could describe the image to a program like Dall-E 2? This software will become more powerful as it allows back-and-forth conversations between the creator and the software. Starting with the image of a financial advisor above, what if I could simply ask the software: “Show me more options for his hands. Shift him a little to the right in the chair. And while you’re at it, let’s put a framed CFA charter on the wall behind him. Not that frame, a brown one.” Adobe’s continued relevance will depend on how quickly and effectively it can incorporate this kind of functionality in its products, and whether alternative software becomes good enough that Creative Cloud no longer seems worth the cost.

The possibilities across creative endeavors are both thrilling and terrifying. Thanks to AI, we’re getting close to the point where “deep fake” videos may become indistinguishable from the real thing. That could mean an actor who’s been dead for 50 years appears in a new film as a young man. It could also mean that a President gets caught up in a scandal because of a fake video, or avoids a scandal because of a real video that he claims is fake! The Internet and social media have already made it harder to distinguish between truth and falsehoods, but that problem is about to get massively more difficult when we can no longer rely on audio or video evidence.

Customer Service

A use case for conversational AI that I’m personally looking forward to is customer service. Chatbots and other automated customer support solutions have mostly been a terrible experience—who hasn’t yelled “Representative Please!” into their phone? But with a limited range of questions and answers, customer support could be a perfect training ground for AI. Forget waiting on hold for 30 minutes, only to be put on hold three more times while the customer support rep tries to figure out your problem. A well-executed AI chatbot could be available 24 hours a day, have all the right answers, and speak in clear, natural language.

Logistics and Self-Driving

Lastly, artificial intelligence could have a profound impact on logistics and transportation, especially if we can figure out self-driving cars. Alphabet has been working on this technology since 2009, and despite many delays and false starts, it seems to be inching toward reality. Waymo (Alphabet’s self-driving subsidiary) now offers a ride-sharing service in parts of Phoenix and San Francisco. Most of these rides no longer require a backup safety driver. Other prominent developers of self-driving technology include Tesla TSLA and General Motors’ GM Cruise.

Self-driving is an extraordinarily complicated task, and many observers doubt that we’ll ever achieve true Level 5 autonomy (where vehicles can perform all driving tasks under all conditions, with zero human involvement). The AI has to deal with an infinite number of scenarios, including many it has never seen before. Driving the wide-open, well-marked roads of a Phoenix suburb on a sunny day is very different from avoiding jaywalking pedestrians while navigating around double-parked cars in the rain in New York City. Regulators have a much lower tolerance for accidents caused by self-driving vehicles compared to accidents caused by human error.

Count me in the skeptical camp on Level 5, at least over the next several years. But even limited autonomy could transform logistics. It could lower the cost of ride-sharing and food delivery. It could improve the economics of trucking compared to railroads or air freight. It could change the parking situation in major cities (by allowing drivers to send cars to park themselves), or it could exacerbate traffic problems. It could greatly improve mobility for people with disabilities. Most importantly, if autonomy lowered the frequency and severity of accidents, it could save many lives, while upending the auto insurance and auto repair industries.

Though less exciting than self-driving cars, advances in AI may fundamentally alter how warehouses operate, too. Amazon has been a leader in warehouse robotics. For example, instead of having workers walk miles every day to find items on stationary shelves, it now uses robots to bring the shelves to the workers, radically improving worker productivity. The main reason humans are needed at all is because of our incredible hand-eye coordination. It’s surprisingly difficult to teach a robot to pick up individual items of varying size, textures, and dimensions. Amazon’s new AI-powered Sparrow robot may be changing that; reports indicate it can already handle 65% of the more than 100 million items in Amazon’s inventory.

What Does This Mean For Workers?

As investors, I expect we’ll need to be even more vigilant than usual over the coming years: Looking for well-managed companies that can benefit from artificial intelligence, while avoiding those that will be disrupted by it. You might say the same about workers. If AI continues to progress at this accelerating rate, what will that mean for customer support representatives? Truck drivers? Warehouse workers? How about lawyers and paralegals? Programmers? Even—gasp—financial analysts?

Artificial intelligence could be very disruptive to the labor market. Many people will not be able to continue doing what they have done in the past. However, that doesn’t mean we’re headed for an era of mass unemployment—or, more positively, mass leisure. Past technological advances had similar disruptive effects. In 1790, about 90% of the U.S. population was farming. With agricultural technology, that number is now less than 2%. The rest of us found other ways to keep busy.

In my view, there are two basic facts that ensure people will always find ways to create value for other people. First, consumer demand is insatiable. It’s human nature that we never have “enough.” That doesn’t necessarily mean a fancier car or a bigger house. It might mean fewer mundane tasks, so you have more quality time to spend with your family and friends. Or trying new restaurants or traveling to farther-away places. Or having better healthcare so you can live a longer, healthier life.

Second is the concept of comparative advantage. We don’t necessarily have to do things better than the robots; we just need to do some things relatively better or more cost-effectively so it makes sense for humans and robots to specialize. It might be possible to build a super dexterous robot who could drive to your house, crawl under a sink, and fix the plumbing—but it’s unlikely to be more cost-effective than hiring a skilled human plumber for $200. Most people would prefer a real human look after their aging parents or grandparents—maybe a robot could cook dinner, but could it reminisce with them over a game of checkers? In the investment world, “robo-advisors” have been around for years, yet most clients prefer to look their financial advisor in the eyes.

The earliest use cases are instructive. GitHub Copilot doesn’t make programmers obsolete: it just makes them way more productive. If there were a limited amount of programming to be done, that might significantly reduce employment in that field. But it seems more likely that Copilot will increase the number of programmers, both because it will require less training to become a good programmer, and because increased productivity will make it feasible to write software for many new applications. The same goes for design and creativity. By lowering the barriers to creating high-quality digital content, it should enable many more people to get creative. Most exciting are the careers we can’t even dream of today: What farmer in the 1790s would have pictured their descendants making money as social media influencers?