We took our son to Disneyland for the first time last spring. As we were herded like cattle from the parking lot to the shuttle buses, one thing was obvious: People love Disney. You could see the excitement in their eyes and their Disney-themed apparel. And I’m not even talking about the kids. At least on that particular morning, it seemed like the majority of the park attendees were childless adults. By the end of the day, we understood: My wife and I had just as much fun as our 7-year-old.

Unfortunately, Disney as a business is a bit of a mess. The stock has gone nowhere for the past five years. Famed CEO Bob Iger recently returned to undo all the changes made by his successor/predecessor, Bob Chapek, during Iger’s 2.5-year absence. Iger deserves a lot of credit for his earlier years as CEO, when he reoriented Disney around its best content franchises and made brilliant acquisitions of Pixar (2006), Marvel (2009), and Lucasfilm (2012). Yet Iger is also responsible for Disney’s current predicament: He was too slow to respond to the Netflix threat, then doubled down on linear TV and legacy content models with the 2019 acquisition of 21st Century Fox, then flubbed the CEO succession process.

Disney celebrates its 100th anniversary this year. I expect it will still be around 100 years from now. But to thrive, Disney needs to embrace the future and finally let go of the past.

Disney Today

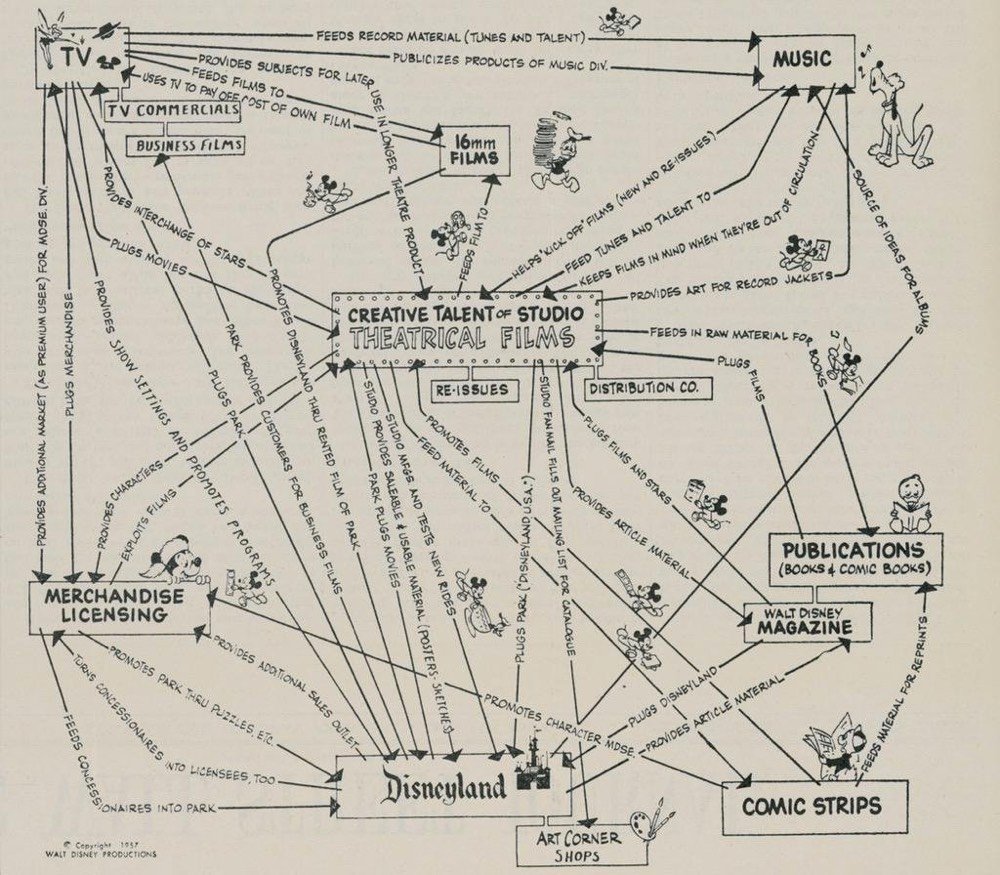

Disney, at its best, is all about content synergies and monetization. It creates characters and storylines that people love and then monetizes them through movies, TV shows, theme park attractions, toys, music, live theater productions, cruise lines, and more. This strategy has worked for decades, as illustrated in this famous 1957 drawing.

Source: Business Insider

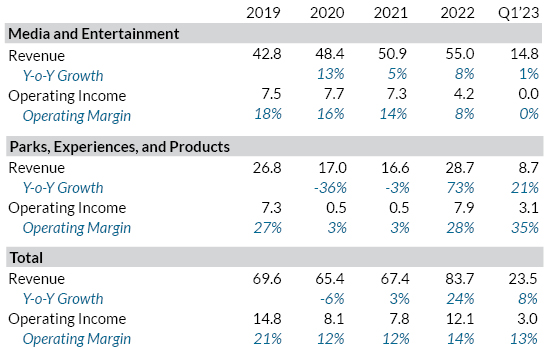

After multiple restructurings, Disney’s financial reporting is also a mess. For the past couple of years, they have split the business into two segments: Media and Entertainment (i.e., content consumed through a screen) and Parks, Experiences, and Products (content consumed in real life). Here are revenue and operating income for each, in billions of dollars:

Source: Company reports.

Disney owns amusement parks in Orlando, Anaheim, and Paris. It also has minority ownership of parks in Hong Kong and Shanghai, and licenses its intellectual property to a park in Tokyo. Not surprisingly, the coronavirus pandemic was tough for the theme park business. The parks were repeatedly closed, and even when they were open they had to operate at reduced capacity. Since theme parks involve very high fixed costs, operating income for the segment was down more than 90% in 2020 and 2021 compared to pre-pandemic levels.

The good news is that the parks bounced back quickly, along with the rest of the travel industry. Despite economic headwinds, consumers are tired of being stuck at home, and they want to get back to enjoying their lives. Disney’s Parks, Experiences, and Products segment set a new record for revenue and earnings in 2022, with operating income 8% above 2019 levels, even as the parks in China have struggled to return to normal operations.

In contrast, Disney’s media business is facing secular disruption. For many years, the company was among the biggest beneficiaries of the pay-TV bundle. Television was our primary source of entertainment, and a cable or satellite package was the only way to get most of the content. At the peak around 2013, more than 100 million households in the U.S. paid for a TV bundle, or about 82% of all households in the country. Disney was arguably the most important content supplier—with channels like ESPN, ABC, and Disney Channel—allowing it to extract ever-increasing affiliate fees from distributors, along with advertising dollars from companies eager to reach a mass audience.

We all know what happened next. Netflix introduced streaming video in 2007, but really started to hit its stride in 2013 with its first original series. That coincided with an explosion of other types of online entertainment, including YouTube, social media, and video games. As entertainment options proliferated, a $100-plus cable subscription no longer seemed like such a necessity. “Cord cutting” proceeded gradually at first—just under a million households canceled their pay TV subscriptions in 2015, 2 million in 2016—but the pace steadily accelerated from there. According to eMarketer, 3.6 million households cut the cord in 2022, and nearly 20 million have done so over the last eight years. That’s a 2.7% compound annual decline rate, accelerating to a 4.3% decline last year. Only about 62% of U.S. households are now subscribers, down from 82%.

It will be interesting to see whether subscribership losses continue to accelerate, or if they might level off as we get down to a core group of loyal pay TV viewers. Either way, things don’t look good for Disney and its legacy media peers. Disney has largely offset lower subscriber numbers with higher per-subscriber affiliate fees, but that can’t go on forever: Those affiliate fees get passed on to customers through higher TV bundle prices, which only accelerates the decline in subscribership. Advertising revenue has also been incredibly resilient, but it’s only a matter of time before advertisers follow eyeballs.

Can Streaming Replace Linear TV?

Streaming is the future of television. From the consumer’s perspective, the advantages of streaming over linear TV are overwhelming: The ability to watch whatever you want, whenever you want, on any device, and with the option to pay for an ad-free experience.

Legacy media companies can no longer sit back and collect affiliate fees from 100 million households while churning out mediocre content loaded with ads, just because they were fortunate enough to be part of the bundle. Streaming is much more competitive, with deep-pocketed new entrants like Apple and Amazon that don’t necessarily care about streaming profitability. Consumers can easily cancel and re-subscribe to individual streaming services, making it much harder to recoup customer acquisition costs. Expectations for the quality of content have gone up, while competition for creative talent has never been more intense. And media companies aren’t just competing with other streaming services—they also have to worry about the million other ways to spend leisure time.

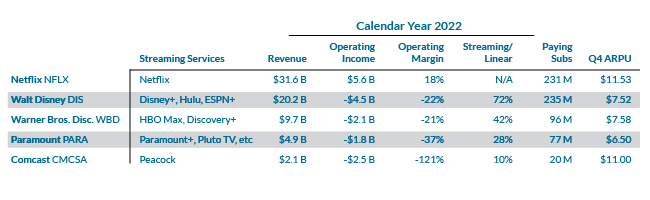

The difficult competitive landscape shows up in financial results. As can be seen in the following table, all of the legacy media companies lost money on their streaming services in calendar year 2022. Comcast’s Peacock was the worst offender, losing $1.21 for every $1 in revenue. “Streaming/Linear” is an estimate of the ratio between revenue from streaming compared to linear TV networks. For example, Disney’s streaming revenue was about 72% of its linear TV revenue last year—by far the highest among traditional peers. “Paying Subs” is the number of paying subscribers as of year-end. Here too, Disney is in the lead, even surpassing Netflix. “ARPU” refers to average monthly revenue per paying subscriber as of the fourth quarter. This is the key metric where Disney lags behind Netflix, since Disney used aggressive promotions to get Disney+ and ESPN+ off the ground.

Source: Company reports, Trajan estimates

So far, the transition to streaming sounds more like a horror film than a redemption story for legacy media, but not all is lost. Streaming has one big advantage over the old pay-TV model: The ability to serve the entire global population. Netflix’s and Disney’s streaming subscribership already far surpasses peak U.S. pay-TV households. There are 8 billion people in the world and more than 2 billion households. While many of these will be hard to access—government content restrictions in China, households with low income, or poor Internet quality in emerging markets—Netflix has estimated its total addressable market at around 800 million households. Furthermore, without the time constraints of a linear TV schedule, the best streaming services can offer content to satisfy any taste.

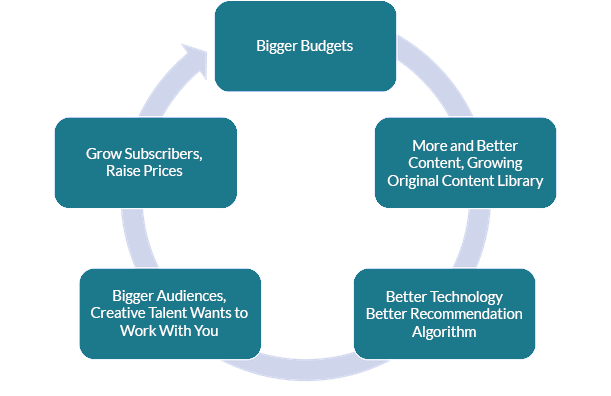

As for profitability, it’s all about operating leverage. Streaming has very high fixed costs but relatively low marginal costs. It costs the same to produce a movie or TV series whether it’s watched by one person or 100 million people. Netflix has already blazed the path: Produce engaging content that people are willing to pay for, attract more subscribers, gradually raise prices over time, and reinvest in even more content, while also expanding margins. Industry leaders tend to have the best technology, the best recommendation algorithms, and an edge in attracting creative talent that wants their work to be seen by a broad audience. Streaming services get better over time as their library of original content accumulates.

Getting that flywheel started won’t be easy, or even possible for most companies. There’s too much competition for our time—who really needs five or six different streaming services? Lesser services (and their investors) are already growing tired of their ongoing losses. They’re pulling back on content and marketing spending. In the long run, it almost certainly makes more sense for a company like Comcast (NBCUniversal) or Paramount to simply license their content to third parties like Netflix.

But for a small group of winners, the prize could be enormous. Ten years from now, could Disney convince 300 million global households to pay $15/month for an all-inclusive streaming service? That would be $54 billion in annual revenue, almost twice the current run-rate from linear TV networks. Content and technology spending shouldn’t need to increase nearly as much as revenue in that scenario, so margins could end up materially higher than they ever were under the former pay-TV model.

Disney’s Next Move

Getting to that happy future requires management to execute much better than it has over the past five years. Bob Iger has outlined three priorities since his return:

He’s putting more power back in the hands of Disney’s creative teams, including authority over what content they produce, how it is marketed and distributed, and ultimate responsibility for profits and losses. Under former CEO Bob Chapek, content distribution had been separated from content creation, which led to a lack of accountability and frustration for creators (for example, if they felt a movie needed to be shown in theaters, but someone else decided to send it straight to Disney+ instead). I’m always in favor of aligning incentives and empowering your best people, so I think Iger has the right idea here.

Second, Iger is planning $5.5 billion of expense reductions to try to move Disney back toward its former level of profitability. Incredibly, Disney’s entire Media and Entertainment segment lost money in the most recent quarter, with losses on streaming and content sales more than offsetting profits from linear networks. Every company has room to improve efficiency, and as Winston Churchill said, “never let a good crisis go to waste.” But Disney needs to tread carefully—they shouldn’t let short-term profitability concerns derail a streaming business with real long-term potential.

Third, Iger wants to refocus Disney around its core franchises, dusting off the playbook from the earlier years of his first tenure as CEO. Disney, Pixar, Marvel, and Star Wars all have devoted fans, and Disney got a few new potential franchises from the Fox deal, including Avatar and The Simpsons. Iger rightly views “general entertainment” content as less differentiated, more competitive, and lacking the synergies with theme parks, consumer products, and other Disney experiences.

That last point hints at the two strategic paths I see ahead for Disney. The company could probably be successful on either path, but trying to straddle both is not working.

Path 1

The first path is more ambitious. It involves Disney being a direct competitor to Netflix, trying to satisfy the entertainment needs of anyone, anywhere. On this path, Disney should not be pulling back on general entertainment content. Disney’s franchises are great, but you’re not going to watch a Pixar or Marvel movie every day or every week. Nor should the company try to churn out franchise content with the necessary frequency to keep subscribers engaged, because that would risk subpar storylines and viewer fatigue.

On this path, it makes little sense to keep Hulu as a separate service. Many people complained that the old pay-TV bundle meant they were forced to pay for content they never watched. But the truth is that bundling is a powerful tool for customer retention and pricing power. If you only care about the Mandalorian, you can cancel your Disney+ subscription as soon as the season is over. But if your wife is watching Abbott Elementary and your son is hooked on Simpsons re-runs, it becomes much harder to cancel.

Hulu has been a big disappointment. The service launched in 2007—the same year that Netflix started streaming—and at various times it was backed by most of the legacy media companies. But split ownership also prevented content owners from ever fully committing to Hulu. That’s still the case today: Comcast owns 33% of Hulu, but it’s been pulling the best NBCUniversal content to put on Peacock instead. And Disney is similarly reluctant to support Hulu if some of the benefits are going to flow to Comcast.

This arrangement never made sense and it should have been resolved years ago. Instead, the companies struck a complicated deal that enables Disney to buy out Comcast’s stake in early 2024. Disney should try to accelerate that decision. If it buys the rest of Hulu, I believe it should be consolidated with Disney+ to maximize bundling advantages. But an even better option may be for Disney to sell its two-thirds stake to Comcast instead, and then move Disney-owned general entertainment content into Disney+. Comcast seems committed to the content business, but Peacock is floundering, and the company doesn’t have a lot of good options. I suspect they would be willing to offer Disney generous terms for full control of Hulu.

There’s also the question of what to do about ESPN. Disney has to thread a needle. It has huge, multi-year fixed costs for sports rights. ESPN is still a linchpin of the legacy pay TV bundle, but if Disney were to offer most of its content through a low-cost streaming service, distributors might drop ESPN so they can offer a lower-priced bundle. At the same time, sports leagues can’t be happy about declining pay TV subscribership—they need their sports to be widely available to maintain fan engagement. And then there are the big tech companies like Apple, Amazon, and Google (through YouTube) that are showing an increased willingness to bid for sports rights, driving up prices.

I’m not sure what the right answer is, but if I were Bob Iger, I would seriously consider bundling streaming service ESPN+ with the rest of Disney’s content, instead of keeping it as a separate service. The same bundling logic applies: If a customer only cares about the NFL, it’s much too easy to cancel a sports-only streaming service when the season is over. But if ESPN+ were combined with Disney+ and Hulu’s general entertainment content, Disney would have more hooks to keep subscribers loyal. Again, the goal should be creating a service that 300 million households would be willing to pay $15/month for.

Path 2

The second path is the opposite approach: Slim Disney down and focus on its core competency of franchise content, monetized through many different outlets. I have a feeling Iger is more inclined toward this path, but it would mean admitting the 21st Century Fox deal was a big mistake and having to make some tough decisions about Hulu, ESPN, and the other legacy cable networks—the sooner, the better.

Disney’s fans are uniquely devoted and enthusiastic about its content. I expect you could build a very solid business just with this core fan base, but Disney needs to be a smaller company. Nobody goes to Disneyland because of ESPN or the latest Hulu drama. If Disney decides to go this route, Iger’s first call should be to Comcast’s Brian Roberts to see if he might be willing to buy ESPN along with Hulu, plus as many other Disney cable networks (Freeform, FX, A&E, etc.) as regulators will allow.

Unfortunately, if Comcast isn’t interested, there aren’t a lot of other potential bidders for these assets. The other legacy media companies are too small and too indebted. Tech companies wouldn’t want to be burdened with linear networks in secular decline. So, Disney’s next-best option would probably be to spin off ESPN and the rest of the networks, including ABC. Disney’s latest re-organization created a separate segment for ESPN, stoking speculation that a spinoff may be in the works. The spinoff could take a decent chunk of Disney’s debt with it, and then be run for cash while trying to navigate a graceful decline.

This path would leave Disney with a single streaming platform, Disney+, but also no linear TV business to try to replace. Core Disney+ (excluding India’s Disney+ Hotstar) had 104 million subscribers as of year-end, paying an average of $5.77 per month. Could that eventually grow to 150 million subscribers generating revenue of $10/month? That would be $18 billion of annual revenue—slightly smaller than Disney’s current direct-to-consumer business, but with a more focused content slate that would allow for much higher margins. And without the distractions of ESPN or general entertainment, Disney could devote all of its attention to what makes it special.