Governments around the world have been flooding the markets with liquidity for much of the past 15 years—first in response to the 2008-09 financial crisis, then because of the slow economic recovery, and eventually because of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic.

In the U.S., Congress ran large budget deficits while the Federal Reserve bought the government’s debt, keeping interest rates near historic lows. Many armchair economists thought this would inevitably lead to inflation, but for most of those 15 years they were wrong. Until now…

The combination of strong demand and supply chain disruptions coming out of the pandemic seems to have finally awoken inflation from its 40-year slumber. The Federal Reserve was late to react and is now scrambling to raise interest rates, hoping not to destroy the economy in the process. The last major bout of inflation in the 1970’s was not kind to investors, who understandably fear an encore.

I’m not much for macro forecasting. I agree with Howard Marks’ latest memo about the impossibility of predicting the future path of the economy, let alone using such a prediction to improve your investment results. Marks described a common scene:

“At the lunch…, people were asked what they expected in terms of, for example, Fed policy, and how that influenced their investment stance. One person replied with something like, ‘I think the Fed will remain very worried about inflation and thus will raise rates significantly, bringing on a recession. So I’m in risk-off mode.’ Another said, ‘I foresee inflation moderating in the fourth quarter, allowing the Fed to turn dovish in January. That will allow them to bring interest rates back down and stimulate the economy. I’m very bullish on 2023.’

We hear statements like these all the time. But it must be recognized that these people are applying one-factor models: The speaker is basing his or her forecast on a single variable. Talk about simplifying assumptions: These forecasters are implicitly holding everything constant other than Fed policy. They’re playing checkers when they need to be playing 3-D chess. Leaving aside the impossibility of predicting Fed behavior, the reaction of inflation to that behavior, and the reaction of markets to inflation, what about all the other things that matter? If a thousand things play a part in determining the future direction of the economy and markets, what about the other 999? What about the impact of wage negotiations, the mid-term elections, the war in Ukraine, and the price of oil?”

We won’t make sweeping portfolio changes in response to the latest macro fear—the probability of getting the timing right is much too low. But we do want to be prepared for any eventuality, which includes owning assets that can grow their intrinsic values even in an inflationary environment. Inflation is one of the biggest risks facing long-term investors; it won’t matter if your portfolio doubles over the next 10 years if the cost of anything you’d want to buy has tripled.

Inflation Hedges and Non-Hedges

My favorite inflation hedge is owning your primary residence, especially if you were fortunate enough to lock in a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage when rates were around 3% (and don’t need to move anytime soon). Everyone needs to live somewhere, which creates a sort of natural liability; housing accounts for almost a third of the average household budget. If you own your house, its value may increase along with inflation, while the cost of a fixed-rate mortgage stays constant. If housing prices decline temporarily, at least you still have somewhere to live. Woe to the renter facing rising monthly costs with nothing to show for it at the end of the lease.

As for liquid assets, short-term bonds, Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, and I-bonds can all provide some degree of inflation protection. Short-term bonds can be rolled into higher-yielding securities when they mature, while TIPS and I-bonds adjust their coupon payments for inflation. By contrast, long-term bonds are one of the worst places to be, as inflation eats into their promised return. In the 80/20 and 60/40 versions of our Expanding Moat and Defensive Moat strategies (the ratios refer to the mix of stocks to bonds), we’ve tended to overweight shorter-duration and inflation-protected bond ETFs. In the current market, we don’t have to give up much (if any) yield for a hedge in case future inflation and interest rates are higher than expected.

A few alternative asset classes—such as gold, commodities, and cryptocurrency—have a reputation as inflation hedges. I find that reputation is undeserved. For example, the price of gold peaked at $850/ounce in early 1980, then averaged $418/ounce through the 1980s, only to fall to a low of $253 in 1999. Anyone who bought gold at the 1980 peak had to wait until early 2008 (28 years later!) just to break even in nominal terms—never mind keeping up with inflation. The track record of crude oil isn’t much better, with those who invested in 1980 losing money for the next 20-plus years. Cryptocurrency is a much newer asset class, but it’s not off to a great start, with Bitcoin currently trading more than 70% below its 2021 peak.

The problem with all of these so-called hedges is that there are many factors affecting their price besides inflation. As in the Howard Marks quote, investors who view them as inflation hedges are using a one-factor mental model. Commodity prices will depend on technology developments, global economic growth, the pace of depletion and new discoveries, construction activity in China, pipeline availability, the Russia/Ukraine war, and many other factors. Gold and Bitcoin are speculative assets in that they don’t generate cash flows and thus have no “intrinsic value.” The main driver of their prices, even in the long term, is investor sentiment. You might have better luck consulting a fortune teller than a government inflation report to determine where they’re headed.

What About Stocks?

That brings me to stocks. The conventional wisdom—at least judging by the market’s reaction on days when there’s bad inflation news—seems to be that stocks are not a good inflation hedge. That’s especially true for the faster-growing companies that make up the core of our Moat strategies. The theory is that these companies derive more of their value from cash flows in the distant future, so they are disproportionately hurt by higher discount rates. I think this is an overly simplistic take.

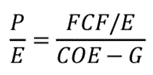

To see why, we need to familiarize ourselves with the justified price/earnings formula, which can be thought of as a very abbreviated version of a discounted cash flow model. I’ll spare you the algebra, but if you assume a company’s cash flows will grow at a constant rate forever, the justified P/E is equal to the ratio of free cash flow to net income, divided by the cost of equity less the growth rate in free cash flow.

There are four ways that inflation can impact a stock’s intrinsic value. In each case, the outcome will largely depend on whether a business has an “economic moat”—a structural advantage that protects it from the competition.

1. Earnings

Before we can think about a reasonable P/E, we need to have an estimate for earnings. The impact of inflation on earnings will depend on how it affects revenue versus costs. Some companies will be able to raise prices in line with or faster than inflation, while holding costs relatively steady. Other companies will see an immediate jump in costs, but be unable to pass any of it through to customers. The implications for near-term earnings will be dramatically different.

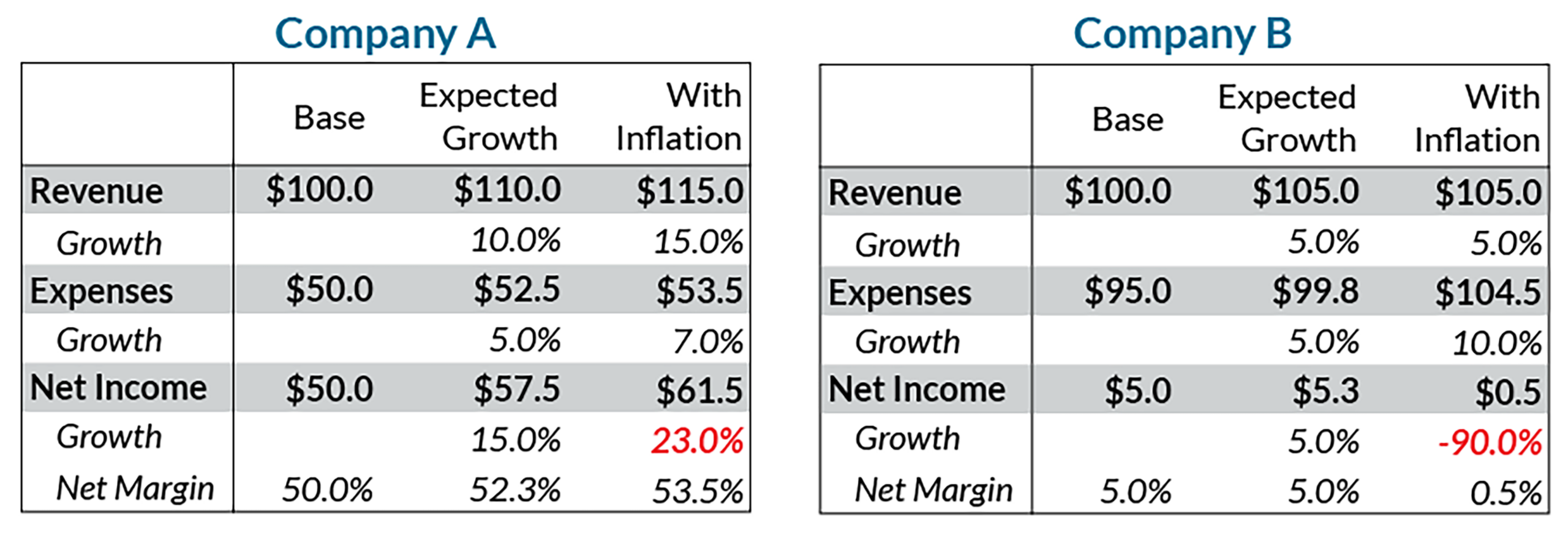

For example, let’s say Company A competes in a rational duopoly with pricing power. It provides an essential service, and its customers face high switching costs if they want to move to the only viable competitor. Better yet, Company A has 50% net margins, and its costs are mostly fixed (long-lived software and computer servers, real estate, a modest staff of already well-compensated employees, fixed-rate debt). The company was expecting 10% revenue growth and 5% expense growth this year. However, with inflation running 5 percentage points higher than anticipated, revenue growth is now expected to be 15%. Expense growth will only accelerate to 7%, thanks to fixed costs and prudent management.

Company B isn’t so fortunate. It participates in a brutally competitive, capital-intensive manufacturing business. If it tries to raise prices, there are ten similar companies that will be happy to steal its customers. Its net margin is an unreliable 5%, and its costs are highly variable—metals, energy, logistics, a large staff of lower-wage workers (who could easily work for a competitor), and variable-rate debt. The company had originally planned for 5% growth in both revenue and costs. It still manages 5% revenue growth, with slightly higher prices offset by volume headwinds as consumers also struggle with inflation. But it won’t be able to pass through the rest of the impact of inflation on expense growth, which is now expected to be 10%.

If both companies started with $100 of revenue, their simplified income statements might look something like Exhibit 1. Company A is better off than if there hadn’t been inflation: Revenue growth accelerated more than expense growth, so margins expanded, and earnings were up 23% instead of 15%. By contrast, the combination of low starting margins and the inability to pass through higher costs was devastating for Company B, where earnings collapsed by 90%.

Exhibit 1: Impact of Inflation on High-Quality and Low-Quality Businesses

Source: Trajan Estimates

2. Free Cash Flow/Earnings

The other potential impacts of inflation can all be seen in the justified price/earnings formula above. Let’s start with the numerator. Free cash flow is typically calculated by subtracting capital expenditures from “cash flow from operations” on the cash flow statement. There are three main reasons why free cash flow is normally below net income:

- Capital expenditures exceed depreciation. This can be the case even if a company isn’t growing its fixed asset base. The company is still replacing old assets (where depreciation expense is based on historical cost) with new assets (where capital expenditures reflect the current price level).

- Net investment in working capital. Most businesses have positive working capital, meaning that accounts receivable, inventory, and other short-term assets exceed accounts payable, deferred revenue, and other short-term liabilities. As the company grows, so will its working capital needs.

- Non-cash revenue and expenses. This might include amortization related to past acquisitions, unrealized gains or losses on investments, asset impairment charges, stock-based compensation, and so on. (In practice, I usually subtract stock-based compensation from both adjusted net income and free cash flow, in which case it won’t affect the FCF/E ratio.)

In an inflationary environment, the gap between free cash flow and net income tends to grow: The spread between capital expenditures and depreciation widens, and companies need to devote more funds to working capital. All else equal, this contributes to a lower justified price/earnings ratio.

However, not every company has free cash flow below net income to begin with. If Company A is truly exceptional, it might get paid by customers faster than it has to pay suppliers, while also requiring minimal inventory or property, plant, & equipment. In this case, inflation may not hurt—and could even help—the ratio of free cash flow to net income.

3. Cost of Equity

Next up is the cost of equity, or the discount rate used to bring future free cash flows back to the present. Cost of equity can be understood as the rate of return required by the average investor. I find it to be the most challenging valuation input because it can’t be observed, even with the benefit of hindsight.

That said, it stands to reason that investors will require a higher (nominal) return in an inflationary environment. They need to be compensated for the fact that prices will be higher when they eventually decide to spend the money. That means higher discount rates—and thus lower valuations—for all assets. This is what Warren Buffett is referring to when he says that rising interest rates are like “gravity for asset prices.” Investors using a one-factor model to conclude that inflation is bad for stocks are focusing on the cost of equity, but they’re ignoring an important potential offset: long-term growth.

4. Growth

The final term in the justified P/E formula is what really separates stocks from bonds. As described in #1 above, the impact of inflation on long-term earnings and cash flow growth will depend on its relative effect on revenue versus costs. If revenue and expense growth both accelerate in line with inflation, then earnings will too. If revenue growth accelerates more than expense growth, as was the case for Company A, inflation could even be a net positive. But if inflation hits costs without a proportionate benefit to revenue, as with Company B, then earnings will grow more slowly or decline.

It’s worth noting that the impact of inflation on earnings may be different in the long run than in the short run. If inflation catches a company by surprise, it’s more likely to hit expenses before revenue has a chance to adjust. But if inflation becomes entrenched, the competitive landscape should find a new equilibrium, with all companies incorporating expected inflation in their prices (otherwise, returns on capital would drop and some competitors would exit the industry). With stocks, faster long-term cash flow growth can potentially compensate for the higher cost of equity: Long-term bonds have no such offset.

So… Are You Going To Give Us Some Tickers?

To summarize, companies that are best positioned for inflation have the ability to raise prices, costs that are relatively fixed, and low capital intensity (i.e., a high ratio of free cash flow to net income). I believe this describes many of the holdings in our Expanding Moat and Defensive Moat portfolios, but two really stand out: Visa V and Mastercard MA.

Visa and Mastercard are the leading open-loop payment networks. Banks pay them for the privilege of putting their logos on credit, debit, and prepaid cards, and then they facilitate the transfer of funds between consumers and merchants. Much of their revenue is tied to payment volumes, which means inflation flows directly through to revenue: If the price of everything is going up, consumers will be spending more on their cards, and Visa and Mastercard will collect higher fees. That’s on top of the secular tailwind from growing global personal consumption expenditures and the shift to digital payments in place of cash and checks.

At the same time, Visa’s and Mastercard’s costs are relatively fixed, as demonstrated by the tremendous operating leverage they’ve enjoyed since their initial public offerings. Once their payment infrastructure is in place, the marginal cost of processing more or higher-value transactions is close to zero. As long as management is prudent with investments and acquisitions, it shouldn’t take much to keep expense growth below revenue growth. Better yet, Visa and Mastercard have minimal net invested capital and routinely generate free cash flow about equal to net income. Inflation might even help cash flow because of their favorable working capital cycle.

I believe Visa and Mastercard have strong and improving competitive advantages. It starts with their network effects: The more merchants accept Visa and Mastercard cards, the more consumers want to pay with them, and the more consumers want to pay with them, the more merchants feel obliged to accept them. That positive feedback loop is reinforced by globally recognized brands, customer switching costs, and economies of scale. The valuations appear reasonable considering their long-term growth prospects, with forward price/earnings ratios of 21.5 for Visa and 23.0 for Mastercard (as of the close on Oct. 3, according to Bloomberg).

That’s not to say Visa and Mastercard are without risk. The coronavirus pandemic proved especially difficult. They generate relatively high fees from cross-border travel, which all but shut down during the pandemic (though it bounced back in recent quarters). They are exposed to regulation and lawsuits, especially regarding interchange fees (which are paid from merchants to issuing banks, but with the level often set by the networks). Consumer surcharges for using credit cards are becoming more common, and regulators have attempted various ways to increase competition in transaction processing. The strong U.S. dollar hurts their international revenue, and they can get caught up in geopolitical issues, such as when they exited Russia following its invasion of Ukraine.

Probably the most serious risk facing the networks is disruption by new payment methods. Visa and Mastercard were mostly locked out of China by regulation, but even if they could enter it would be too late now thanks to the dominance of mobile payments such as WeChat Pay and Alipay. Other emerging markets are hoping to control their own payment systems with government-sponsored programs such as Brazil’s PIX and India’s RuPay and UPI. Some bearish observers see this trend spreading to developed markets with instant-payment services like FedNow in the U.S., along with digital wallets like PayPal and Cash App.

So far, I believe Visa and Mastercard have done an admirable job navigating these threats. Emerging-market payment systems might curtail their long-term opportunity, but in the short run they’re only helping to accelerate adoption of digital payments. On its last earnings call, Visa management commented that Brazil payment volumes on its network have more than doubled since 2019, while India volumes are up 84%. The companies (especially Mastercard) are also helping certain governments build and operate real-time payment systems, and providing services like fraud prevention and dispute resolution.

In the U.S. and Europe, new financial technology startups and mobile wallets like Apple Pay have been far more likely to partner with Visa and Mastercard than try to compete with them. Working with the incumbent networks provides instant access to the long tail of small merchants, cross-border acceptance, and a robust ecosystem of credit providers, rewards, chargeback functionality, and fraud prevention. Trying to recreate all that from scratch to avoid Visa’s and Mastercard’s modest network fees simply isn’t worth it.

Talk To Us Today!

If you’re interested in learning more about how Trajan Wealth can help you meet your financial goals,

please visit us online or call 1 (800) 838-3079.